English

King’s English programs provide the pleasures and challenges of reading closely literary texts of our own time and many other periods and places. We offer courses in all the major historical periods of English, from medieval through contemporary; national literatures in English, including British, Canadian, American, and Postcolonial; courses in literary theory, drama, popular literature, film, children's literature, creative writing, and more.

In our small classes and seminars, our students acquire knowledge and skills in analysis, writing, and public speaking. Our graduates thereby prepare themselves for careers in, for example, education, publishing, law, marketing, media and communication, public relations, business, and industry.

In addition, the study of English allows us, as Wallace Stevens put it, to find ourselves "more truly and more strange." Come study with us, and see how reading, writing, and thinking about literature can cultivate a lifetime of curiosity, wonder, and pleasure.

For Ontario high school students a minimum 80% final entrance average is required. Averages are calculated on the top six 4U or 4M credits including English 4U.

College transfer students are required to have a minimum cumulative average of "B" or better in an acceptable one-year certificate (General Arts and Sciences, Pre-Health Science, Human Services Foundation) or completed diploma. College transfer students may earn up to a maximum of five transfer credits. Individual courses must have a minimum achievement of 60% to be considered for transfer credit.

King’s projects a minimum 65% for admission for students transferring from another Canadian University. A maximum of ten transfer credit may be granted. Individual courses must have a minimum achievement of 60% to be considered for transfer credit.

For students with a keen interest in English, Philosophy and History, please check out our limited entry first year program: Foundations in The New Liberal Arts for a comprehensive interdisciplinary approach.

This is a course about two things: storytelling, and learning to be analytical about it, on the one hand, and expressing oneself eloquently once one has acquired these analytical skills, on the other.

Why are they important? Well, storytelling is as central to being human as anything else is: speech, tool-making, upright posture, all the various features that have been put forward, at one time or another, as “distinctively human.” As Peter Brooks puts it, “Our lives are ceaselessly intertwined with narrative…. We live immersed in narrative, recounting and reassessing the meaning of our past actions, anticipating the outcome of our future projects, situating ourselves at the intersection of several stories not yet completed.” Storytelling is, as philosophers like to say “constitutive of our identities”; that is, we make sense of ourselves, and we communicate what kind of people we are, through stories. What could be more important, then, than learning how the best storytellers have told their stories? Reading Homer and Austen and Dickens and Tolstoy and Joyce gives us a firmer grasp not just of technical storytelling techniques but of our own selfhood, our own capacity for moral choices and fine discriminations. For centuries, narrative has seduced us into morality as well as sociability. From the epics of blind or anonymous storytellers, through medieval religious narratives, to the novel and the film, and finally to the (as yet) largely untheorized narratives typical of the age of Facebook and other social media, narrative has been our teacher and guide. What could be more important, then, than to pay attention to these shaping forms of narrative?

The other aspect of the course is just as important: expressiveness, articulateness, eloquence. It is precisely these skills that are most in demand in the world outside the academic humanities. A good English course teaches you to think well, and to express yourself well. I firmly believe that English departments are the true heirs of the classical discipline of rhetoric, the art of persuasion. Here, if anywhere in the university, there is an emphasis not only on what you say (or write) but how you say it (or write it). In an age in which social media, paradoxically, may intensify “connectivity” while paralyzing actual face-to-face verbal and communicative skills, it often falls to English courses to take up where rhetoric left off. It is in courses such as this one that students learn to organize their thoughts, take up a position in a debate, express themselves clearly, politely and eloquently, and participate in the unending adventure of human intellectual inquiry.

Is the Internet making us smarter or stupider? Have we sacrificed in-depth analysis for informational breadth? This two-part linked course investigates the impact of new technologies on the storyteller’s art. If storytelling defines who we are and how we relate to the world, what is the status of storytelling in a digital age? What are the effects of technology on our reading practices and our writing practices? More broadly, ENG1027/8 examines the relevance of the liberal arts as a discipline in an increasingly technocratic world.

The first half of this course (1027) explores the rich and diverse traditions of storytelling, from oral tales and short stories to classic fiction and the graphic novel, with an emphasis on developing strong analytical and writing skills. Particular attention is placed on the fundamentals of narrative theory: plot, point-of-view, focalization, persona, and the roles of the author, narrator, and reader.

The second half of this course (1028) focuses on digital story-telling and the extent to which the fundamentals of storytelling have been abandoned, transformed, and/or retained by new digital media. We will consider examples of online collaborative story-telling, Facebook as life writing, tweeting and blogging as critical engagement, YouTube/Vimeo as self-publication, and interactive fiction-games such as 999: Nine Hours, Nine Persons, Nine Doors and Digital: A Love Story to ask how new digital technologies have radically transformed storytelling, for better or for worse, into a widely accessible platform for self expression.

Shakespeare remains one of the most influential of English writers. This course studies twelve plays across a range of genres. Instructors may integrate theatre-oriented exercises and/or other dramatic or non-dramatic material, depending on individual emphasis. When possible, the teaching program will include an autumn theatre trip.

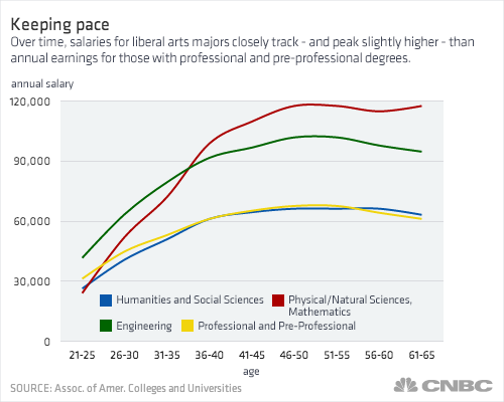

English graduates are prepared for a variety of professions. In the fast-paced and changeable career dynamics of the 21st century, the skills learned in reading literary and critical texts are basic to success in our knowledge-based economy.

In January 2010, The New York Times, investigating changes at the University of Toronto’s Rotman School of Management, reported on a "radical idea in business education: that students needed to learn how to think critically and creatively every bit as much as they needed to learn finance or accounting. More specifically, they needed to learn how to approach problems from many perspectives and to combine various approaches to find innovative solutions."

Approximate Costs

Fee details and schedules are available at www.kings.uwo.ca/fee-schdeules/