Colby Cosh: When Acadians and Mik'maq coexisted in a state of peaceful anarchy

Acadia turns out to be a rarely noticed exception to the historical pattern of violent frontier conflict on this continent between the primordial occupants and the European invaders

Article content

Two economists, Rosolino Candela and Vincent Geloso, have a new economic history paper, which explores an enigma of the Canadian past: why do Acadians and Mi’kmaq seem to have gotten along so well? The modern Acadian identity is naturally that of a displaced people victimized by ethnic cleansing. Our image of them, for better or worse, is established at the moment of their attempted removal from the British Empire and influenced by their subsequent evolution. But Acadia as it existed in its heyday may be important to understand.

Right now the paper is a preprint, but it is scheduled to appear in Public Choice, the leading journal of (wait for it) public choice economics. Geloso, an economic historian at Western University’s King’s University College, is part of an anarchist-influenced tradition within that strongly libertarian field of scholarship. Candela is at George Mason University, the world capital of public choice. If you’re a traditional leftist (or a left-anarchist), this paragraph is a consumer warning. If you’re like me, you’re excited that these people even exist.

Anyway, Acadia turns out to be a rarely noticed exception to the historical pattern of violent frontier conflict on this continent between the primordial occupants and the European invaders. Almost everywhere else, between Christopher Columbus and the “closing” of the North American frontier, settlers lived in heavily structured colonial societies, which answered to European governments and were able to call on their armies and navies when their local predations against the Indigenous led to warfare.

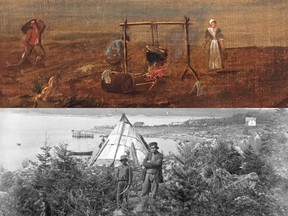

The Acadians nestled in the Bay of Fundy were different. Old royal France, which consciously engineered early Quebec and used local seigneurs as tax farmers and instruments of policy, mostly ignored the few thousand Acadians. Farmers developing the Acadian marshlands did not pay tax to the old country, though they were capable of public works, and their systems of land title and self-government were informal and consensus-based. They were off on their own quasi-anarchist planet, more or less — but one surrounded, on higher ground, by Mi’kmaq neighbours.

Those neighbours were even more anarchistic, as anthropologists have frequently attested. Their non-coercive town hall-style systems of collective decision-making mirrored those of the Acadians. Did bloodshed and chaos result?

Quite the contrary: the documented history of violence between the Acadians and the Mi’kmaq rounds readily to a big fat zero. The two groups settled into complementary roles in the global economy, with the Mi’kmaq harvesting furs and trading them with the Acadians for food and European technology. Both prospered and began to intermarry. Credible estimates of Acadian wealth from before the 1755 “removal” suggest that it was not only richer than New France, but was probably richer than the original — i.e., France itself.

Under the jewellers loupe of public choice theory, this is a “raid or trade” situation. Neither the Acadians nor the Mi’kmaq were able to offload the costs of organized violence onto a “higher” state. Each group was well armed, but neither was able to appeal to a far-off capital full of sentimental taxpaying cousins to help settle any differences. It certainly must have helped that the Acadians, as expert dyke-builders, were physically creating much of the land they occupied and exploited. No Mi’kmaq could have a claim on territory that had not existed before.

We all know how the story ends: the Acadians’ productivity incited jealousy in the Massachusetts colony, and the Acadians themselves, who had been permitted by the British authorities to remain “neutral” and go about their business, found themselves objects of suspicion and eventually elimination. If they were anarchists, they met the expected end of an anarchist society: destruction by a nearby state possessing a professional apparatus of violence. The ultimate results, needless to say, weren’t great for the Mi’kmaq, either.

It’s important to understand that when public choice scholars study anarchistic settings that once might have been called primitive, they are not necessarily making a positive argument for anarchism. Maybe anarchist polities have characteristic advantages we can imitate (or fake). Maybe they don’t scale up well. Maybe it is just a law of history that armies and police are medicinal in appropriate quantities and toxic in greater ones.

But whatever one’s own political principles, Acadia (a name that is basically another word for “Utopia”) hints at an answer to the question constantly before us all: could the great encounter between North America’s Aboriginal peoples and European colonizers have been more peaceable and friendly? We must surely believe it if we are to believe in interracial coexistence at all, and the answer Candela and Geloso provide tentatively is: “Here is a place and a time in which it actually was that way.” If you like, you can complete the sentence: “and then the British ruined everything.”

National Post

Twitter.com/colbycosh

Postmedia is committed to maintaining a lively but civil forum for discussion. Please keep comments relevant and respectful. Comments may take up to an hour to appear on the site. You will receive an email if there is a reply to your comment, an update to a thread you follow or if a user you follow comments. Visit our Community Guidelines for more information.