Ethics and Morality

What Makes Us Different?

A clear picture of the transition from primates to persons.

Posted August 24, 2018

This article was co-authored by Dr. Joseph Michalski, Associate Dean at King’s University College at Western, Canada.

This rather extended blog on what makes humans different first reviews a recent Scientific American (September 2018) issue and then offers a novel extension that ties the pieces together. In discussing this topic, it is important to put a clear frame on it up front. Any “what makes us different” analysis must guard against excessive “anthropocentrism,” which declares humans are worlds away (and worlds above) all other animals. Such a notion is obviously at the center of the Christian narrative, which ruled most Western Civilization for the past 2,000 years. In the last 100 years, there has been a swing back against species centrism, with some arguing that humans are merely dominant, but not exceptional in any other way. This counter argument also clearly has limits. It is simply an empirical fact that humans live different kind of lives than other animals.

In his book, The Marvelous Learning Animal, Arthur Staats points out this difference in terms of “behavioral repertoires,” which refer to the patterns of activity and investment. Think here of eating, sleeping, defending territories, playing, cooperating, searching for mates, avoiding predators, making nests, and so forth. With about 20 categories, Staats argues we can classify the vast majority of animal behavior. That is, for all animals except humans. The complexity and differentiation of human behavior is qualitatively different (starting with reading this blog, think of all the different kinds of activities you have done today, such as driving, doing laundry, dropping kids off at daycare, chatting about politics, etc.). In short, to get this issue right, we need to be clear about both the ways in which we are similar to other animals in general (and primates and great apes in particular) and the ways we are different.

Part I of this blog delineates several key components to think about humans relative to other animals in the Scientific American issue. Several intriguing and compelling threads were offered, but they were not tied together in a way that offers a clear picture of the whole tapestry.

Part II argues that the Justification Hypothesis, in combination with the Tree of Knowledge System, pulls together the puzzle pieces and offers a clear and coherent vision for both how we are like other animals and what makes us different. In doing so, we are finally able to have a clear and justifiable narrative for how we are both continuous with and yet differentiated from other animals.

Part I: Laying out the Puzzle Pieces

To achieve a full picture of our natures, the developmental psychologist Nancy Link argues we need to track the evolution of human mental capacities via our phylogenetic and our ontogenetic past. That is, we need to understand how both animals in our evolutionary line and children think, feel, and act, as well as identify and track how they change over time.

Our starting point for understanding animals and the animal mind is Behavioral Investment Theory (BIT), a formulation that integrates cognitive neuroscience, ethology and evolutionary psychology, and behavioral learning theory. For a 50 min video on animals’ “brain power” that corresponds closely to the vision afforded by BIT, see here.

Humans are a particular kind of animal, a great ape. As vertebrates, we humans have a “perceptual-motivational-emotional’ system that serves as a behavioral guidance system. As mammals, we have a developed cortex that allows for “higher, imaginative thought.” This is the ability to simulate events in one’s mind and make choices based on those simulations. For example, brain images of a rat at a choice point in a maze demonstrate that it simulates the two options (based on past experience) and then chooses according to the anticipated reward/effort investment. As we will see, advanced capacities for mental manipulation of the environment is one of the important puzzle pieces that likely contributes to our distinctiveness.

As primates, we are very social mammals. Social animals live rich lives, and in Beyond Words: What Animals Think and Feel, Carl Safina has offered a wonderful compilation based on naturalistic observation of elephants, orcas, and wolves. Social mammals have distinct temperaments, keep track of who their friends and enemies are, what their status is, and what they can and cannot do in the social group. The 5-minute clip on macaques in the previously referenced Brain Power video that starts at the 35th minute is a great example of the complicated social network analyses that macaque monkeys use as they navigate the dynamics of sex, power, cooperation, and competition. Another wonderful example is the now famous “cucumber-grape” video by Frans de Waal. It offers a clear example of monkeys having an intuitive sense of fairness. The differential treatment (the monkey receiving a cucumber rather than a grape for the same task) activates frustration and anger, just as it would in a human.

With this background in place, we can turn to the Scientific American (SA) special issue entitled Humans: Why We Are Unlike Any Other Species on the Planet, and review the puzzle pieces it offers about human distinctiveness that are currently being explored by leading experts.

Brain Structure and Anatomy

Sherwood and Schumaker point out that one of the most striking features of the human brain is its size, and especially the size of the cortex. (Some have claimed that growth has been especially pronounced in the prefrontal cortex, but that is disputed; interestingly, attention is now turning to the cerebellum). The cortex is the portion of the brain that fosters mental simulation. Mental simulation is when you move objects and situations around in your mind. The “lower brain” has perceptual-emotional-procedural parts that guide action in context. For example, seeing a predator and freezing or running away. The cortex is involved in integrating and extending information to guide more complicated action patterns. The back portion consists of three lobes (occipital/vision; temporal/auditory; and parietal body/spatial position) that integrate perceptual information and facilitate the manipulation of images, whereas the frontal portion regulates impulses and plans out sequences based on consequences. The human brain has grown dramatically in these areas, when compared with other great apes.

General Learning and Cognition

Given that the cortex is involved in the simulation/manipulation of scenarios, it is consistent that humans should have distinguished capacities for representing and manipulating the world in their minds. Indeed, one of the key abilities that sets humans apart cognitively is the ability to think about representations, an ability some call “metarepresentation,” such as Dan Sperber. In the SA issue, Suddendorf describes a similar ability, which he calls “nested scenario building” and describes as “our ability to imagine alternative situations, reflect on them and embed them into larger narratives of related events.” In short, humans have capacities for perceptual reasoning and mental simulation that combines elements into a whole and allows for much greater flexibility and extension, especially relative to time (i.e., mental time travel).

Social Cognition and the Urge to Interact

Suddendorf argues that nested scenario building combined with a social drive to connect and share, such that the combination of the two drove human difference. Kevin Leland emphasizes a similar point in his “cultural drive” hypothesis. This is the idea that humans are excellent innovators, willing teachers, gifted copiers, and skilled at transferring information with high fidelity. When combined, these cognitive and social interactive elements potentially create an accelerating feedback loop.

Human Language

How is it that humans are effective at transferring information with much greater fidelity than other animals? One obvious answer is language. Of all the things that make us different, talking is arguably the most salient. As a recent article on the evolution of human speech and vocal chords put it, “Language is the mechanism by which the aggregated knowledge of human cultures is transmitted, and until very recent times, speech was the sole medium of language. Humans have retained a strange vocal tract that enhances the robustness of speech. We could say that we are because we can talk.” In the SA issue, Kenneally reviews the fact that nailing down the evolution of language and specifying its uniqueness has been more complicated and controversial than one might expect. She argues that language does not emerge via a “switch” or a single capacity, but from a combined suite of abilities. Those abilities include the urge and capacity to share information and pass information down across the generations. In this view, it was not that human language gave rise to human culture, but that the engine of culture (i.e., social engagement and interaction) gave rise to language. This raises the question of what is meant by culture.

From Animal to Human Culture

Leland defines “culture” as comprising of “behavior patterns shared by members of a community that rely on socially transmitted information.” Using this broad definition, other animals clearly have culture. There are famous cases of monkeys learning to wash potatoes and crows learning to crack nuts before passing these patterns on to others. But, Leland notes, there is clearly a gap in the way humans transmit information relative to the other great apes. Language and advanced cognitive capacities (social and nonsocial) served as a complexity-building feedback loop that drove human cultural evolution into a qualitatively different domain. In his landmark book, The Origins of the Modern Mind, Merlin Donald argues for a three-stage view of human culture. First, there was “mimetic culture,” in which humans were able to symbolize via gestures. Then “mythic culture” arose from the acquisition of speech and the capacity to weave narratives together. Finally, there was technology-supported culture, which involves ever increasing capacities for communication and external memory storage (like writing).

Technology (and How It Changes Us)

Although it is now well-documented that some other animals use tools, there remains a qualitative difference in the complexity and diversity of human technology. Indeed, it is literally changing the entire world. Dartnell, Mayo, and Twombly specifically explore the intricacies of the combustion engine and how it reveals our collective genius. In a much earlier era, as David Christian discusses in Origin Story, agriculture changed the way we related to the environment and that, in turn, changed us. And the impact of modern technology on the very essence of our being has been powerfully explored by Marshall McLuhan. In many ways, we have been defined by print, electricity, radio, television, and now, the digital age. As Domingos notes, it seems clear that our future lives will be enormously shaped by our relationship to and transaction with artificial intelligence.

The Question of Consciousness

As one ponders what it means to be human, issues emerge at the very heart of our understanding of existence. This brings us to the nature of consciousness, explored in the SA issue by Susan Blackmore. She notes that although our subjectivity is obvious at one level, it is hard to study objectively. Perhaps even more difficult is the explanation for how the neurophysiology of the brain gives rise to the felt experience of being. Philosophers and scientists are still struggling with how to frame this issue, and to do so in a way that is congruent with and helpful for empirical investigation. She highlights that one of the more popular conceptions is that the theater of consciousness functions like a global workspace, initiated by the cognitive scientist, Bernie Baars (see here). Another angle considers consciousness as integrated information. Interestingly, these two models give different answers to the question of animal consciousness. The workspace model argues that only higher, vertebrate animals are conscious, whereas the integrative information model suggests much more of a general continuum that could even stretch into cells without a nervous system.

Blackmore then discusses the philosophical “illusionists” who argue that subjectivity and the experience of a self are the byproduct of the brain and a function of focused attention. Daniel Dennett has developed the “multiple drafts” theory to explain the process. In this view, thoughts and perceptions “are continually processed, and none is either conscious or unconscious until the system is probed and elicits a response. Only then do we say the thought or action was conscious; thus, consciousness is an attribution we make after the fact.” Blackmore counts herself among the illusionists, especially when it comes to self-consciousness, and concludes her article with the claim that, “we humans are unique because we alone are clever enough to be deluded into believing that there is a conscious ‘I’.”

Morality, Meaning Making, and the Concept Personhood

As Blackmore notes, central to the issue of consciousness is the issue of suffering. If other animals are conscious, then they can suffer and that carries important moral implications (see Sam Harris’, The Moral Landscape). This brings us to another aspect of human uniqueness, morality. Tomasello sees the evolution of human cooperation and interdependence as central to our “beingness.” He suggests that a sense of “we”ness permeated our social organization as cooperative hunter-gatherers. When this combined with the emergence of language, what evolved are cultural norms that regulate behavior, both explicitly and internally. He argues that, “Modern humans thought of the cultural norms as legitimate means by which they could regulate themselves and their impulses and signal a sense of group identity. If a person did deviate from the group's social norms, it was important to justify uncooperativeness to others in terms of the shared values of the group (“I neglected my duties because I needed to save a child in trouble”). In this way, modern humans internalized not only moral actions but moral justifications and created a reason-based moral identity within the community… The immediate concern for any individual was not just for what ‘they’ think of me but rather for what ‘we,’ including ‘I,’ think of me.”

In this light, the “I” becomes not so much an illusion, but an important psychosocial interpretter and regulator of behavior. It navigates the explicit intersubjective world, created by humans as they chatter amongst themselves and try to make sense of their very “beingness.” Peter Ossorio offers an important, but often overlooked, analysis that is relevant here. He argues that the defining conceptual features of a “person” is an entity that can self-consciously reflect on and justify one’s actions on the social stage, and be held accountable for them by others. The analysis separates out the concept of a person from a human being.

In science fiction, for example, we can see clearly the idea that a person need not be a human being. Jabba the Hut, the famous worm-like creature that captured Princess Lea in Star Wars, was a person in this sense, but clearly not a human being. Of course, so is God, at least as envisioned by the theistic religions. In his wonderful book, God: A Human History, Reza Aslan explores the evolution of religious beliefs and, in particular, the vision of God that has emerged since the time of agriculture. His conclusion is that God reflects an innate human tendency to project meaning onto the universe and especially human-like capacities on the ultimate forces that guide it. Aslan writes, “Whether we are aware of it or not, and regardless of whether we’re believers or not, what the vast majority of us think about when we think about God is a divine version of ourselves.” As Montesquieu once observed, “If triangles had a God, they would give him three sides.”

In reviewing these “puzzle pieces” and imagining them placed out before us on a grand table, the question emerges as to whether or not we can use our mental manipulation and social exchange capacities to see if there is a way to fit the tapestry of threads together to see the whole picture? Is there a way to tighten this narrative by weaving together a story that: (a) locates humans as primates, (b) takes into account the emerging advanced capacities for abstract thought, along with (c) social exchange, teaching, and cooperation that (d) points to the evolution of human language that supercharges the essence of (e) human culture in a way that accounts for (f) human self-consciousness, (g) morality, (h) social norms, and (i) the concept of personhood, while fitting with the remarkable emergence of (j) technology and facts about how the (k) acceleration of human society is changing us as we peer into the future?

We believe that the answer is yes. There is a missing piece in the above formulation, however, that helps tie these many pieces together. Without it, we are left with a diverse array of related threads, but no completed picture. That integrative feature is known as the Justification Hypothesis.

Part II: Tying the Pieces together with the Justification Hypothesis

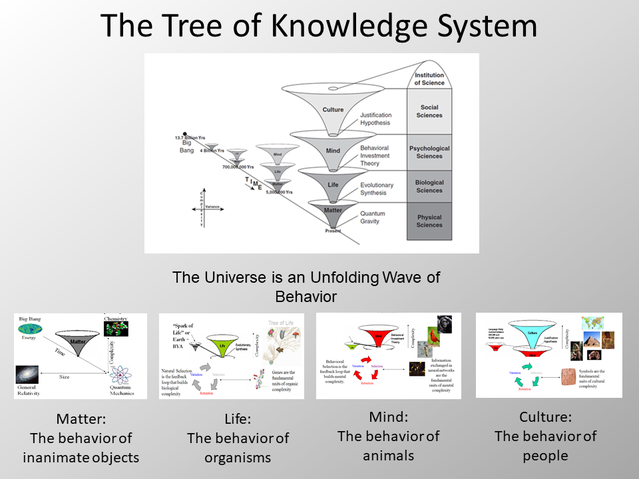

The Tree of Knowledge System is a new way to conceive of the universe and our place in it. Specifically, it depicts the universe as an unfolding wave of behavior that exists across four different dimensions of behavioral complexity: Matter, Life, Mind, and Culture. These dimensions correspond to the behavior of inanimate objects, organisms, animals, and people. The emergence of each dimension is associated with a complexity-building feedback loop. The Mind-to-Culture complexity-building feedback loop that resulted in primates becoming people is called the Justification Hypothesis. It is the missing puzzle piece that ties everything together.

Many of the articles in the SA issue emphasized the idea that there must have been a complexity-building feedback loop that pushed human evolution in a different direction. Suddendorf explicitly argues that the cognitive capacity of nested modelling coupled with the urge to connect created the feedback loop that resulted in the key features that make modern humans distinct (which he lists as culture, morality, language, abstract explanations, mental time travel, and mind reading).

To clarify what the Mind-to-Culture joint point on the ToK System represents, we start at the top of the Mind cone, which is where our non-linguistic ancestors (e.g., Australopithecus afarensis) exist, as do modern apes. The first major, clear technological innovation happened more than 3 million years ago, when stone tools first appeared on the scene. A million years passed without much activity. Tool use had expanded by 1.8 million years ago, but was still not dramatic. The evidence then points to another major innovation, the controlled use of fire, by Homo Erectus around 600,000 years ago.

From a SA “puzzle piece perspective,” four key pieces are likely involved and setting the stage for the complexity-building feedback loop that is about to explode onto the scene: (1) the brain is enlarging; (2) nonsocial cognitive abilities are expanding; (3) there are increasing levels of social involvement and coordination; and (4) technologies such as stone tools and then fire are starting to have a major impact. But we do not yet have either full language or full self-consciousness – nor any type of fully developed human Culture (noted here with a capital "C"). The best current evidence suggests that hominids other than Homo sapiens had proto-linguistic capacities. Estimates on the evolution of language range from 500,000 to 70,000 years ago, with most pointing to approximately 100,000 years ago.

In addition to the emergence of language, another important feature of the evolutionary landscape is how things start to change dramatically as revealed by the kinds of cultural artifacts found in the archaeological record. From cave paintings, to fish weirs, to burials with ornamentation, we see an explosion of change. This shift started perhaps 75,000 years ago, which was clearly in full swing by 30,000 years ago. Such a significant and dramatic shift often is referred to as the “Human Mind’s Big Bang,” or the dawn of modern humanity and of mythic culture. This acceleration between 100 and 50 thousand years ago represents the best time frame for the “Mind-to-Culture” joint point.

Here is the basic story, according to the framework provided by the Justification Hypothesis. The combination of an increased cortex, increased meat eating that is cooked, increased social complexity, and a proto-language resulted in the emergence of a full language system likely about 100,000 years ago. Full language differs proto-language because the latter uses disjointed nouns and verbs that are mixed with gestures to convey meaning about concrete events in the here and now. As we will see, full language is a game changer.

Why do humans develop symbolic language? The main argument suggests that the combination of sociality and increased mental abilities, combined with changes in the vocal chords, set the stage. In terms of cognitive capacity, the likely element here has to do with an increased working memory that allows for more sophisticated and extended forms of mental manipulation. This then is coupled with a “symbolic tagging capacity,” which refers to the unique human ability to “tag” a representation held in the mind with a symbol.

If we put mental manipulation with symbolic tagging together, then we get the basic “shape” of human language. We can recognize the tagging of objects and the fields they occupy as “nouns.” We can recognize the changes over time as “verbs.” And we can recognize the differences between entities as “adjectives.” These are the fundamental ingredients to virtually all language systems. There may be some exotic exceptions, but generally nouns, verbs, and adjectives are the foundational conceptual elements of language. When such symbols are arranged in syntax, an open representation system is born.

Here is where the central insight of the Justification Hypothesis (JH) kicks in and provides a framework to understand the evolution of human self-consciousness, humans as persons, humans as reason givers, and the unique aspects of human Culture.

As an informational system, language allows for much more direct connection to the individual’s subjective perspective on the world. Think about how much easier it is to understand your spouse’s view of the world as compared to your dog. Language interconnects human minds and creates a highway of intersubjectivity. This is great for coordinating and creating shared understandings.

However, it comes with a major issue. We are now capable of being held responsible not only for our actions, but for our thoughts, feelings and intentions. In the JH formulation, this is the problem of (social) justification and represents a completely novel state of affairs in the animal kingdom. It also turns out to be the key missing link that results in a fundamentally “tighter and cleaner” picture of the whole than any other model.

First, the JH identifies a specific new adaptive problem faced by our ancestors. The other strands of thought explore some feature that is known about humans (cognitive ability, bigger brains, language, etc.) and then create narratives about how this or that made the difference. The JH is a game changer because it specifies a new and central adaptive problem that makes very clear predictions about: (a) human reasoning; (b) human consciousness; (c) human Culture; and (d) the nature of personhood. Full language resulted in questions about one’s subjectivity, which forced the development of the ability to create and analyze justifications for “why one does what one does” and “why the world is the way it is.”

We are the justifying animal, or Homo justificationem. We build personal and social systems of justification. This is an entirely new dimension to social life and social organization. It becomes the glue that coordinates social rules and provides insights into our belief-value systems. What is remarkable about the idea is how it ties everything together. It clarifies the building block pieces (bigger brains, social motives and coordination, mental abilities) that set the stage for the emergence of language, which in turn sets the stage for a whole new dimension of existence, justification systems. When we, as a psychologist and sociologist, respectively look at human existence through the lens of justification, we are able to see human psychology and human culture through a much clearer, cleaner light.

Consider the nature of human consciousness. As a clinical psychologist, Henriques is particularly interested in the dynamics and domains of consciousness and how they are connected to suffering. The JH allows for a whole new way to understand human consciousness. Language created a world of explicit intersubjectivity, whereby others have potential access to one’s subjective consciousness. As such, that means we are able to “see” our consciousness and report on what we are seeing. And it means that we can divide human consciousness into the subjective, experiential theater portion, the private self-report, and the public, intersubjective portion connected via talking. It follows directly from the JH that these domains should operate based on different constraints and that there should be filtering between them. In fact, we can look at modern research in human consciousness and see clearly that the JH assimilates and integrates data and theory from cognitive science (e.g., global workspace theory, System 1 and 2 cognitive processes, research on human reasoning reviewed by the book Enigma of Reason), modern psychodynamic theory (the Freudian filter and primary versus secondary processes, cognitive dissonance and defense mechanisms), and social psychology and microsociology, among others that explore things like impression management.

But it is not just at the human psychological level the JH makes sense. Think for a moment about human cultures. What lies at the center of human cultures? Shared belief-value systems that legitimize aspects of the world, provide norms and moral forces, frame roles and actions, and structure our personal identities. What are these, but large-scale systems of justification? And what is a “person,” if not an entity that can enter into social discourse, be “socialized” to what is justifiable, and then be held accountable (by herself and the social field) for those actions? From a sociologist’s perspective, Michalski argues that the JH provides a clear frame for what Leslie White described as “culturology”: the science of human culture.

In sum, between 100 and 50 thousand years ago, a process was set in place that would give rise to a whole new dimension of complexity, i.e., the dimension of Culture that we humans now navigate as persons. Our person self-concept is the justifying regulator of our actions. And, because justification systems evolved and can be transmitted with high fidelity relative to other aspects of human communication, it has been cumulative. Unlike other models that take what we see in the here and now and then attempt to construct the past, the JH places the key puzzle piece in place and then specifies how humans should reason, what the dynamics of self-consciousness should be, and what the form of shared belief systems should take. That is, the JH is not about the past. It is about the here and now. It specifies what we are, what we are doing, why we do the things we do. Indeed, the JH provides a bridging component not only to understand the emergence of the person, but social behavior in general (e.g., cooperation, altruism, violence, and so forth) and eventually the creation of large-scale groupings and institutions.

Finally, we want to conclude by noting that the JH does not bring the story of cosmic or even human evolution to a close. In the first place, we live in open, dynamic systems that constantly require energy inputs to fight off the second law of thermodynamics, or “entropy.” That means that the interactions of humans beings in their environmental contexts, situated in their historical locations, and with available technologies are always subject to the ecological and survival pressures that have existed since time immemorial. Even our conception of “what is a person” is dynamic and evolving as a natural byproduct of our increases in self-understanding, the cultural narratives and “formation stories” we share, and the leviathan of technology that constantly helps shape and reshape our experiences as highly evolved apes that we currently label “Homo sapiens.” But, as Harari discusses in Homo Deus, that may profoundly change in the not-too-distant future. To guide this change process in an adaptive direction, it is crucial that a shared understanding of our natures emerges sooner rather than later.